What is a design system?

No matter where you go, you are surrounded by systems. We use the word ‘system’ to describe a group of interacting parts as a common whole, and these can be simple, like a watch, or incredibly complex, like the web of computer networks we call the internet. In this book, the term ‘design system’ is used to describe a philosophy that encourages designers to define the rules of their designs as a system of instructions that can be used on more than a single product. This is best explained with a simple story.

Let us suppose I am asked to design a label for a local brewery’s famous stout beer. I want to make sure that my design is a good fit for the product, so I spend a lot of time researching and tasting the beer before making my final design. The brewery loves my new design, and they ask me to design labels for the rest of their 10 beer types. Now I am faced with a problem. The colors, typography, and illustrations I chose for my label design was a great fit for a strong and dense beer, but it will not work for the other beers. So I end up creating labels with a different visual style for each beer, but without a consistent branding for the brewery.

This problem could have been avoided had I designed the first label with the conviction that it would be a part of something bigger: A design system for the brewery. Instead of focusing on the particular stout, I would have defined a range of visual styles to be used for different beer types. This would include a set of related typefaces and colors with enough variance to be used for the individual beers, but recognizable enough to provide a common identity for the brewery. Only after creating this design system would I design the first label.

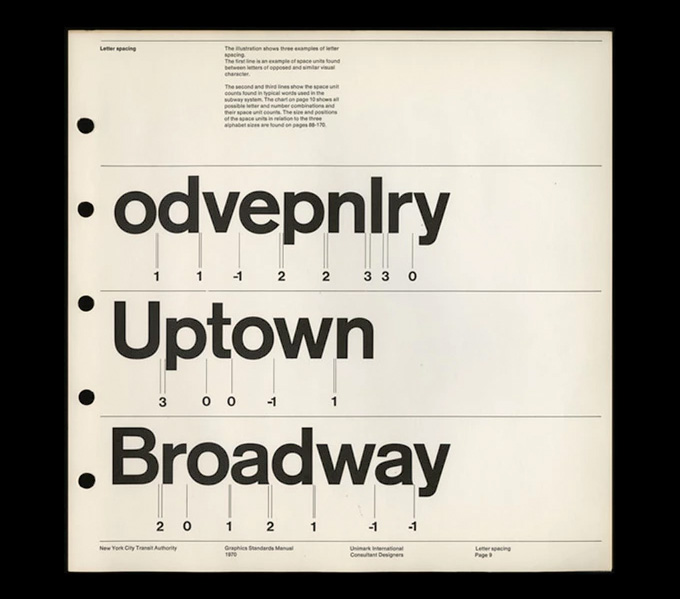

Design systems offer a different way of thinking, where the designer is forced to consider many scenarios and constraints instead of relying on a one-off design process. This approach is of course nothing new, and some might say that it has always been a part of the designer’s job. Thousands of design systems have been created over the years, from the New York Transit Authority Graphics Standards Manual to Google’s Material Design. Most Fortune 500 companies are recognizable for a reason: they have defined strict rules for use of typography and color across their product line.

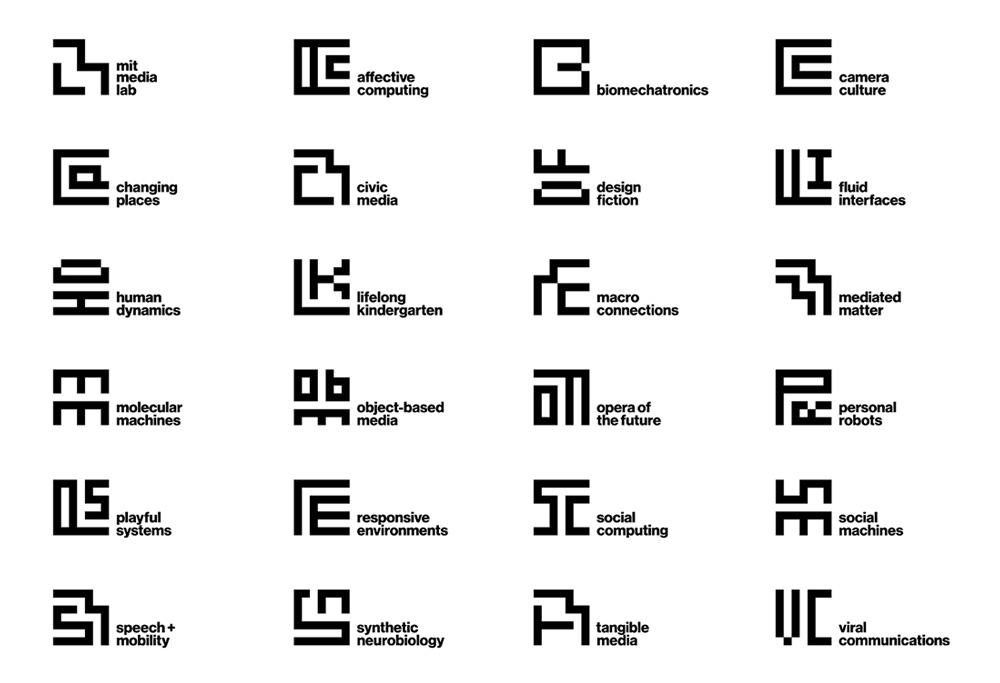

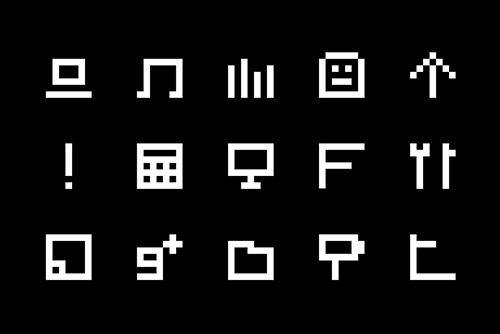

A recent example of a simple design system is the MIT Media Lab logo created by Pentagram. The idea is simple: Fill a 7x7 grid with perpendicular lines to create abstract letters or symbols in black and white. This system is used to create logos with acronyms for the 23 research groups at the lab, and as a basis for building a custom typeface, icons, and patterns.

This logo is an excellent example of how a design system can be used to give both a consistent look and a distinct style to an organization. The system is both simple and flexible, and it has room for an almost infinite number of designs.

Design systems are especially interesting today, because digital products are systems, and designers who code are no longer confined to the creation of design systems that end up in printed manuals. Code allows designers to not just create designs, but build digital systems that create designs. Granted, more time will be spent on formulating the rules of the system in code, but designers will be free from the limitations imposed by traditional design software. The American computer scientist Donald Knuth writes about this very thing:

“Meta-design is much more difficult than design; it is easier to draw something than to explain how to draw it. One of the problems is that different sets of potential specifications cannot easily be envisioned all at once. Another is that a computer has to be told absolutely everything. However, once we have successfully explained how to draw something in a sufficiently general manner, the same explanation will work for related shapes, in different circumstances; so the time spent in formulating a precise explanation turns out to be worth it..”

Donald Knuth (1986), The Metafont Book

The words “sufficiently general manner” are important here. Software can be written to allow a range of possible outputs, and variations of a design system can be generated in (literally) fractions of a second. The ability to procedurally generate designs is one of the most empowering aspects of algorithmic design, whether it leads to generating 45,000 variations of a logo, building an infinite galaxy of planets with generative landscapes, or creating a dynamic article that changes its content based on map selections.

In this book, we will investigate what designers can build when they are encouraged to create design systems and make these systems come to life by writing software.